Why Are Americans So Entitled?

Reflections on culture, the state, and how Americans insist on pulling out their laptops when they should be enjoying life.

I’d like to experiment with Substack to road test impressionistic road-test them, invite feedback (and criticism), and then hopefully I can then further refine the idea or argument for something more substantive and permanent.

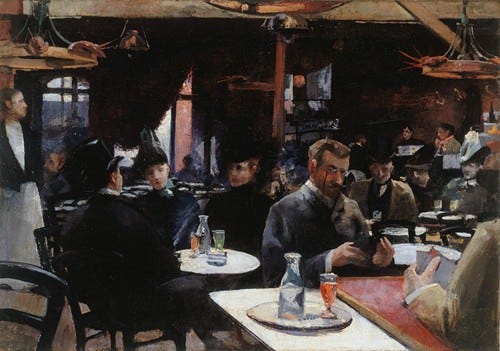

As I alluded to cryptically in my previous post, I have been in France the past week, and I have been reminded of, shall we say,…