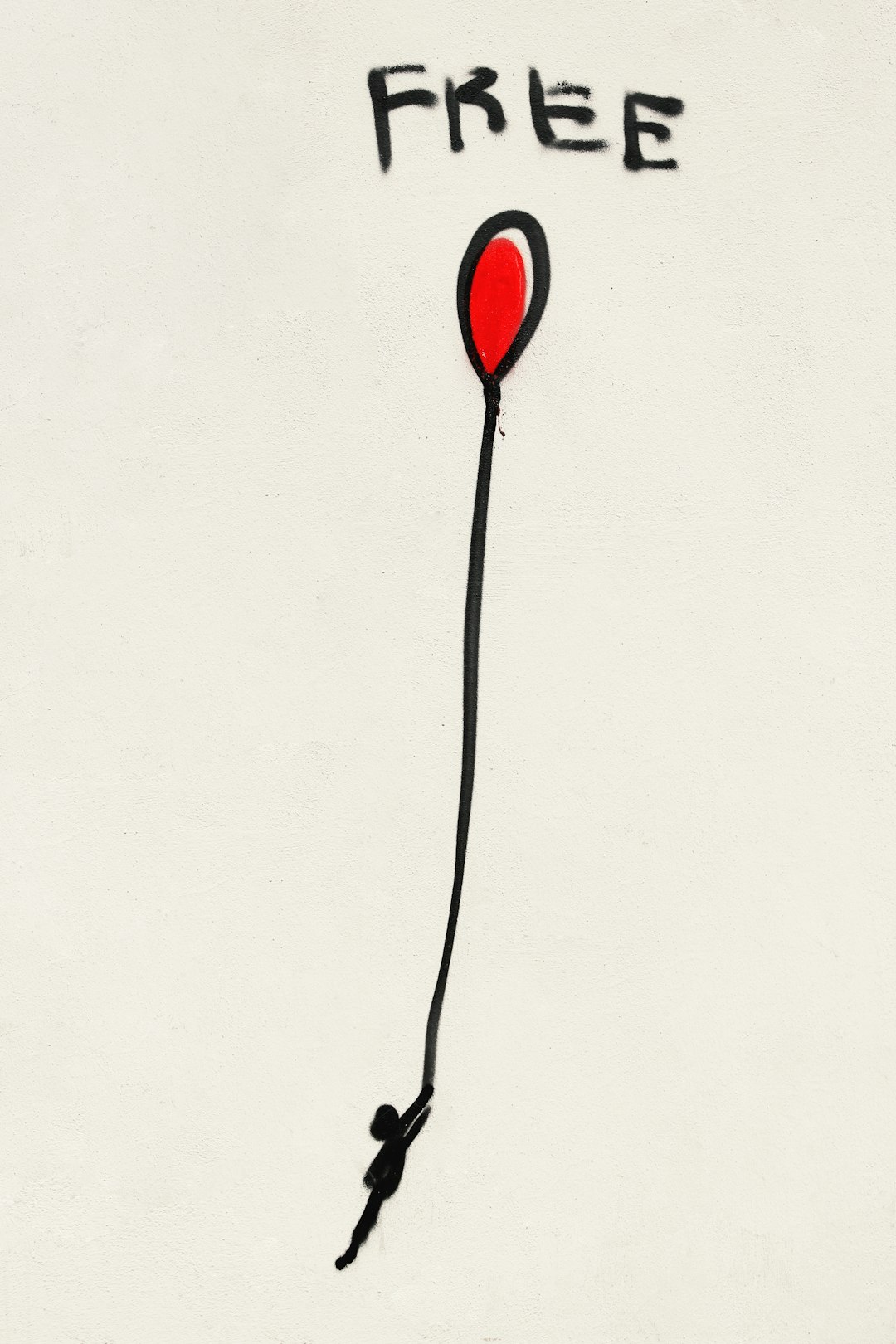

Is Freedom Good Only if You Use it Well?

The "worthiness" of an idea, a goal, a hope is an inherently subjective matter.

In his introduction to James Salter’s A Sport and a Pastime, the American novelist Reynolds Price notes that “winning a freedom and then proceeding to employ it worthily are two decidedly different matters.”

I was struck when I came across this sentence. I am reading A Sport and a Pastime for the first time (after having declared, perhaps in overwrought fashion, that Salter’s Light Years was the greatest novel of the 20th century). The overarching question that both haunts and animates my book on “the problem of democracy” is a version of Price’s distinction between having something and then using it well.